Untranslatable words often carry a variety of deeper and complex distinct meanings which do not find a perfect equivalent in the target language. From the Yaghan mamihlapinatapai to the Portuguese saudade, these words are often meant to represent the feeling a particular sound, smell or memory, a meaning-laden glance or even encapsulate a specific way of life (like in the case of hyggelig in Danish). Some of these words are better-known now that the public is becoming increasingly attuned to multilingualism and multiculturalism, and a lot of these untranslatable words are tied to the concept of love.

Like with every good and terrible thing, love is difficult to describe in one’s own language. It is this important, all-consuming, ever-present concept. Love keeps philosophers and teenagers alike awake at night; love for money, or for your family, or for your job drives that promotion at work; love of discovery and wanderlust pushes humans towards exploration, love of power drives political change, love builds and destroys religions.

One of the most basic translation conundrums every linguist will become acquainted with are the Greek words for love: agape, eros, philia, storge. This article is not the place to talk about the connection between philosophy and linguistics, however the philosophical perception of these words was heavily affected by their understanding and usage in Ancient Greece. Likewise, the meaning of these words when used outside Greek, carries automatically a philosophical connotation. It can be difficult to separate the two, especially when stripping these words down to their most utilitarian level, but breaking them down gives us a better understanding of how they work in Greek and how they could be transferred to other languages.

In English for instance, the word love is a bit of a “catch-all”: you can love pie, but you can also love your dog, boyfriend, that song, this painting, God or the spring — it’s obvious that the connotations attached to each instance give it a different meaning and are adjusted to the context. However, many languages seem to have expressions for different ‘grades’ of affection, longing and desire.

- Agape (love, adoration, loving kindness) Although Agape as a term was present in before the advent of Christianity, it is most closely associated with godly, spiritual love, or the love that God has for man because of its use in the Greek version of the Bible. Agape is a pure form of love, it is a combination of eros and storge — Soren Kierkegaard in his Works of love believed that man needs to show love first to one’s self, in order to be able to love God and his creation. In Modern Greek, agape is the general term for established, safe, tender, solid, life-long love. It is very much of the kind that is expressed in Paul’s first letter to Corinthians. The closest equivalent in Irish is Grá, whereas the closest equivalent in French and Italian would be amour and amore. That being said, while these words are working equivalents, they still do not match the level of intensity and abandon expressed in agape.

- Storge (affection, tenderness, fondness, loving care) Storge is the familial, sweet, considerate love. The kind that wraps you in a blanket and kisses your forehead, the kind that a parent will feel for their child, and a child might feel for a small bird. Storge is deep, nurturing and careful. Cion is the close equivalent in Irish, whereas affection and affetto are the words in French and Italian which could be used to describe it.

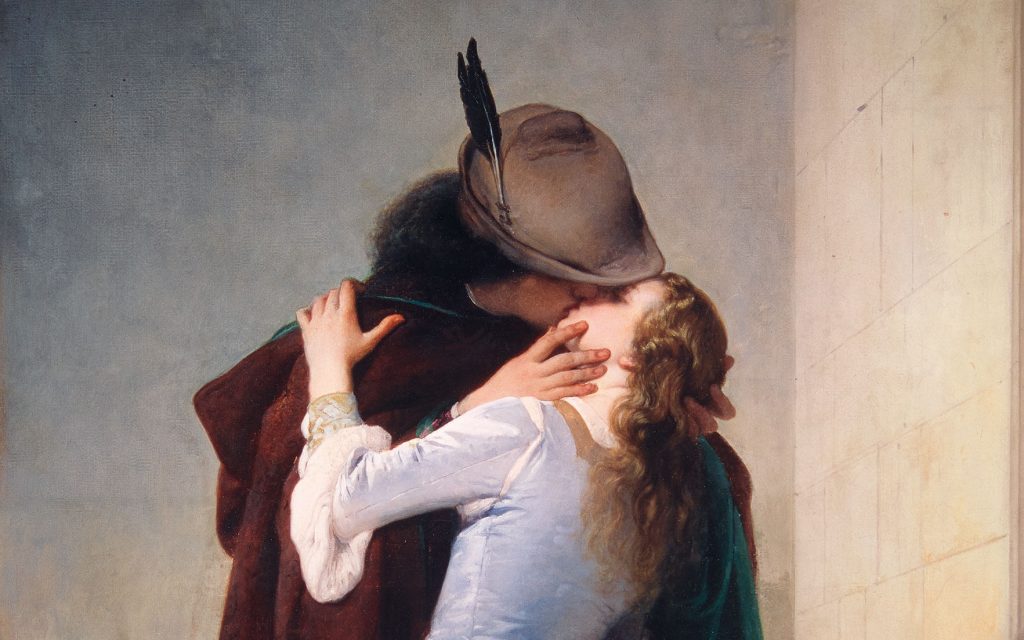

- Eros ([being in] love, infatuation, passion, sex) Eros is the passionate, consuming love. Eros is what someone feels at the beginning of a relationship, before it morphs into agape. In Plato’s work, it is associated with aesthetic love and appreciation of beauty, as opposed to the sexual connotations encountered in languages other than Greek nowadays. In Greek mythology, Eros is the son of Aphrodite and Ares — Aphrodite, goddess of beauty and Ares, god of war. Not for nothing, Eros is passionate, fiery, capricious and breath-taking. As mentioned above, Modern Greek does not directly associate it with sexual love and desire — however its derivatives in other languages (erotic, érotique, erotico) are definitely sensual.

- Philia (friendship, fellowship, mateship, kinship) Philia is the friendly love. Plato and Aristotle put specific emphasis on kinship between equals in a dispassionate, virtuous way – this is also the reason why one would often refer to it as Platonic love. Philia would never encounter Eros, but it is the sort of love based on mutual respect, understanding and admiration. The closest Irish word would be cumann, French has amitié, compagnie, concorde, whereas Italian has amicizia, compagnia, fratellanza.

None of the above kinds of love precludes the other, and they all can be felt at the same time, for the same person, but not for the same object. The beauty of language is that it will develop and adapt to the context of the source while undergoing the process of translation. So even if English has only love to show for it, that is enough in the hands of a capable linguist and… love is enough, really.

*For further reading, we recommend Tim Lomas’s, The flavours of love: A cross-cultural lexical analysis.

Lomas T. The flavours of love: A cross’cultural lexical analysis. J Theory Soc Behav. 2018;48:134—152. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12158